There are good ideas that turn out to be good ideas, like the paper clip, or the safety pin. And then there are those good ideas that turn out to be not so good, like the automatic seat belt in cars. Or like Leanne Shapton’s Important Artifacts etc.

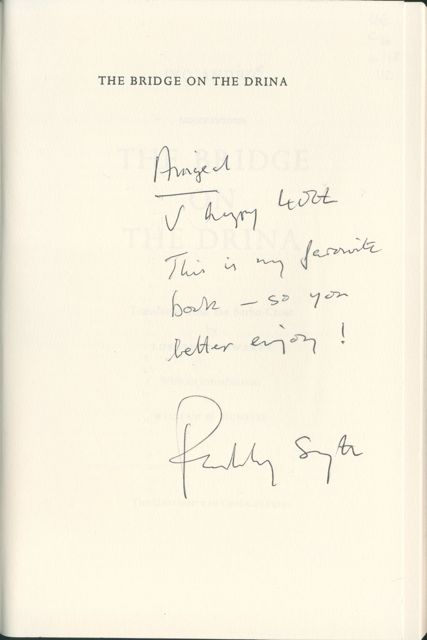

It sounded so promising: in order to tell the story of a couple’s affair, the book pretends to be the illustrated catalogue of the sale of their belongings after they break up. The 300 lots that make up the catalogue are organized – conveniently enough – chronologically, so we get the whole arc of their affair from the initial encounter up to their peak and down to their break-up. The objects range from clothes and books and foods and drinks and artworks to toys and photographs and letters and films and CDs.

To an extent, it works: it’s immediate (this is the actual stuff their relationship was made of), it’s intriguing (what exactly is this stuff?) and it’s intimate (these are the things they gave each other or wrote one another for their eyes only). Also, identification can be immediate (hey, I’ve got that! I’ve read that! I’ve seen that!). And who doesn’t like hearing about the beginnings of a love affair, the efforts that are put into a relationship in the early days, efforts that initially seem so effortless but later seem to demand so much effort? Who hasn’t been through it at least once?

And the idea to tell that story through mere things is not great but also very courageous. That’s the thing about objects: they seem to speak to us in some way or another, but they are ultimately mute. Shapton uses a passage from Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair (what else?) about an ashtray from the lady’s side of the bed: ‘If ashtrays could speak, sir,’ says one character, to which the other replies ‘Indeed, yes.’ But of course that’s the irony of using this quote for this type of book, because the ashtray ultimately tells you nothing. You may be able to tell the story of the ashtray, but the ashtray itself will virtually tell you zilch, nada, nix, nothing – unless you have the same ashtray and then you might recognize the other owner as one of your tribe.

Do the objects here tell us anything? Not much about the characters, unless that they are apparently very hip New Yorkers with a fetish for all things fashionable and trendy and hip. This is no ‘ordinary’ couple selling off ‘ordinary’ things: these two have a certain taste for certain new and vintage objects of certain brands at certain prices as well as for certain writers and certain artists etc. Is there anything wrong with that? Of course not, except that their choices all seem to be dictated by the same principle or idea: it has to be hip, which gets a bit tiresome. And the objects in themselves don’t reveal much about the couple besides the type of couple perhaps, but not the actual people – and certainly not about their story. Neither do all the homemade ‘cutesy’ things like little menus, and handmade gifts tell much of a story: they ultimately become more embarrassing than anything else.

So to get around that, Shapton has to include lots of print-outs of e-mails and handwritten notes and whatnot, which is stretching belief a bit, since one wonders who would, not only pay for this type of stuff, but actually take the time to catalogue it for sale at auction? If the stuff they wrote was even mildly interesting, why not. But consider this: ‘I want it to be perfect.’ Or ‘Dad – not enough love, mother – too much love.’ The things these people write, the things these people think.

The problem ultimately is that the accessories of their affair, the trappings of the relationship outshine the relationship. There is in fact no relationship to speak of: all we get are the props of that relationship: but they tell us little about the actual emotional relationship between these two human beings. They never ever come to life individually, let alone as a couple. The photographs of them that Shapton includes doesn’t add any depth to them either: they remain on the surface.

Shapton claims she got the idea from an auction catalogue of Truman Capote’s belongings in 2006 (the catalogue is online on Bonham’s website). Capote, of course, was famous, unlike Lenore and Harold. Still, looking through the catalogue, it’s amazing how much of it seems to be of rather little interest to anyone but a few people: who would be interested in buying his old suits – old suits, perhaps, but Capote’s old suits? Some of his stuff will be of interest to the literary historian, other things will be of interest to the relic hunter, or someone just looking for a bargain. I don’t know what the catalogue tells us, nor do I know quite what Shapton’s catalogue tell us.

Perhaps it tells us that objects are in fact more interesting than people. Perhaps it tells us that we don’t know how to tell stories and all we know is how to talk about our stuff and show photos of our stuff and of ourselves and perhaps even to try to sell ourselves and our stuff to make a buck.